Rice might not come to mind when discussing American food crops, however, it has been grown here since the late 1600s. There are two types of rice – one is an aquatic “lowland rice” and the other is “upland rice”. The primary reason for growing in water is weed control – rice grows in water while weeds do not. Upland rice will grow with decent rainfall much as do cotton or corn.

Rice has been grown primarily in South Carolina, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas, and western Tennessee but they are not the only states with a rice culture. Today rice is grown commercially primarily in Arkansas (the U.S.’s top producer), California, Missouri, South Carolina, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas but has been successfully grown in Florida and as far north as Vermont and Maryland. Cooler climates will need to start the rice in seed trays and transplant the plugs when plants are at about three weeks growth.

The origin of rice growth in America dates from 17th century South Carolina. “The cultivation of rice spread rapidly from the beginning into most of the Southern States, and even so far north as Missouri, Tennessee, and Illinois.”

Upland rice culture in Mobile was reported in the American Farmer in January 1824. The author stated he saw no real difference in the bearded rice and the smooth and grew both. He noted the bearded had a larger head and larger grain and he felt it was far more productive.

Upland rice was submitted by a farmer in Grand Bay, Alabama which met with praise from the proprietor of the Empire Parish Mill in New Orleans in 1871. “The rice sent by you to our mill will compare favorably, as to the grade and yield, with the best ever raised in Louisiana and will command the highest price in our market”.

“All qualities and descriptions of land have been sown in rice, from the stiffest of clays to the lightest sands, with apparently equally profitable results…”.

South Carolina planters said in 1851 that they planted the upland rice and cared for it just as they had corn but thought the rice produced more food for their families. Crab grass could choke out the rice until it grows large enough in a few weeks to make do on its own. The same writer noted that the rice was as easily transplanted as onions.

Upland rice culture was rapidly increasing in all the flat country bordering the Gulf and Atlantic in the 1870s with some saying the white was the best for upland areas while the famous gold rice of South Carolina and Georgia was the best for water culture.

Growers reported that following the War Between the States as Louisiana’s sugar production plummeted, the production of rice exploded from 7,000 to nearly 30,000 barrels. Comments on the successful production of upland rice as good as, “that which is raised in the swamps of Georgia and South Carolina”, were found in numerous publications including “The Southern Farmer”.

“This has been proved beyond a question in Alabama where for many years upland rice has been raised with great success, yielding 50 to 100 bushels of shelled rice (rice with the husk on) to the acre…The big white, little white, and the red-bearded all do well on upland.”

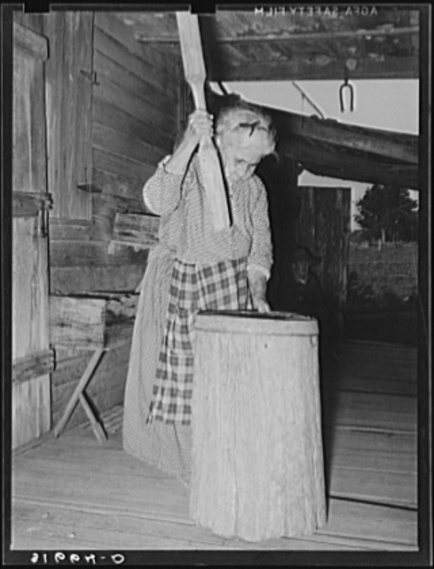

Early on, South Alabama did not have facilities to process rice necessitating shipping to and from New Orleans, however, by 1871 it was said, “the cleaning or hulling can be easily performed with an ordinary pestle and mortar, and at very little expense three or four of these pestles and mortars could be so constructed to be run by the gin power which would clean a large crop with great expedition.”

In warmer climates, sow the seed where it is to grow after soaking in water for between one and five days, changing the water daily. Plant one ounce of seed per 100 square feet soon after the last expected frost date. There should be about four seedlings per foot with rows a foot apart. Plan to use bird netting on T-posts over your crop so it doesn’t become bird food. As with any open pollinated seed one can save seed from this year’s crop to plant again next year.

Harvest begins in late summer after the seed heads turn brown. Cut the stalks and hang them up in a dry place to dry. Thresh it as soon as it is dried.

Remove the rice from the stalk with a flail or by beating the stalks together over a clean sheet or piece of plastic or put the seed heads into a five-gallon bucket and use a drill with a paint stirrer attachment to separate the grains. (Insert the stirrer through a hole in the bucket lid so the rice doesn’t fly out everywhere). Scoop up the rice and drop it with a fan blowing to separate and blow away the chaff. Spread the rice in the sun to dry or it can be dried in a low temperature oven.

An article published in 1924 touches on hulling rice. “The hulls are removed by passing the grains between revolving millstones, set apart about two-thirds the length of a rice kernel…”. The idea is to strip off the hull without crushing the rice grains.

For home production the hulls can be removed by pounding with a rubber mallet or using a large old-fashioned mortar and pestle. There are plans online for making an apparatus to do this and, sites offer hullers for purchase starting at roughly $150 on Amazon. Some of the expensive grain mills can utilize a de-hulling attachment. The attachment itself is $275.

The hulls may be used as mulch, soil conditioner, bedding for poultry, insulation, etc. Rice straw can be used as feed, bedding for animals, mulch, and fertilizer. From the “Mobile Register”, quoted in “Southern Farm and Home March 1873: “…if you do not [have a hulling mill nearby] it will still pay you to grow it as a feed crop, for it bears two cuttings in the year below 32° north latitude and makes a hay which sheep, horses, and cattle prefer to the best grass product grown”.

In the following video we first see a demo of the huller being used followed by instructions on how to build it. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YxWI5Mvw36Y. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xpZxS3QoWTE shows the same machine with a motor attached.

This huller is made from a bench grinder. One wooden grinding wheel stays stationery while the other is turned by the bench grinder. There are some in use in third world countries that utilize one such grinding wheel turning against a plain rubber wheel. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-fnP-y8_Asg

A manual on growing upland rice: http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/ivc/docs/uplandrice.pdf

Seed may be purchased from Nature and Nurture Seeds, AmkhaSeed in Colorado, Experimental Farm Network (as nonprofit in Philadelphia), Sherck Seeds in Indiana, Fedco Seeds, Wild Folk Farm in Maine (they do sell varieties suited to the South as well), Southern Exposure Seed Exchange (they also have a tutorial for growing upland rice), etc.

The Carolina Gold rice seed offered by Baker Creek is a paddy type rice requiring flooding for cultivation.

Blissful Meals and Enjoyable Gardening should readers want to try their hand at rice culture!

You must be logged in to post a comment.