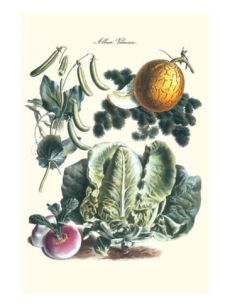

A nice gentleman contacted me recently with a question about 18th century lettuce and I promised to share some information. His question was about period recipes for cooking lettuce and whether lettuce then was anything like what we have now.

Long leaved, cos type lettuce is ancient and depicted in wall and tomb paintings as early as 4500 B.C. Lettuce is found among plants accompanying the Egyptian god, Min [4th Millennium BCE].

Cabbage-leaved lettuce is traced from 1543. Columella knew a few different varieties, and documented the Romans eating young tender lettuce and cooking older and tougher lettuce. They ate lettuce with hot dressing on it much like the wilted lettuce salads popular in the 20th century. Lettuce was cultivated to improve its texture and flavor and by the medieval era there were distinct varieties of three types – heading, loose-leaf, and tall or cos. William Woys Weaver credits the name Romaine, a cos, to it being grown in the papal gardens of Rome, although the name Romaine isn’t commonly found until the latter third of the 19th century.

“Adam’s Luxury and Eve’s Cookery”, 1744 is a good early source showing varieties during the 18th century. Some of those listed are available through heirloom seed companies. Dr. Weaver, in his heirloom vegetable treatise, tells us some of the early varieties later underwent name changes requiring some gardening knowledge to identify them and locate seed. For example, Green Capuchin is now Tennisball and Silesia is now White-Seeded Simpson or Early Curled Simpson.

Cos lettuce was common during the 18th century. Accounts such as the one from “The New London Family Cook” instructing the gardener to tie up the leaves of cos lettuce, “the same as endive”, to shield the inner leaves from the sun rendering them tender and crisp indicates that without special care some lettuce was tough. The center leaves would have been preferred for salads while the outer leaves would have benefitted from cooking.

Jamie Oliver’s braised peas and lettuce

Lettuce that formed a loose head was called cabbage lettuce and that which produced tall leafy to very loose-headed plants was cos. The varieties were divided further by season – that which could withstand a European winter, spring lettuce that headed rapidly, summer lettuce which were usually larger than spring lettuce and which tolerated more heat without bolting as fast. Cutting lettuces never form a head and are harvested a few leaves at a time as the plants grow. This is sometimes referred to as cut and come again. Southern Europe also had a, “perennial lettuce”, which resembled dandelion.

Lettuces varied in depth of color from very pale to very dark green.

In John Randolph’s eminent Gardening Treatise penned in 18th century Virginia, we see the cutting lettuce, Cabbage lettuce, and cos. Randolph found the cabbage lettuce the least pleasing of the three. “This sort of lettuce is the worst of all the kinds in my opinion. It is the most watery and flashy, does not grow to the size that many of the other sorts will do, and very soon runs to seed”.

Randolph found the cos the, “sweetest and finest”, because it washed the easiest, it remained longer before bolting, and, it was the, “crispest and most delicious of them all”.

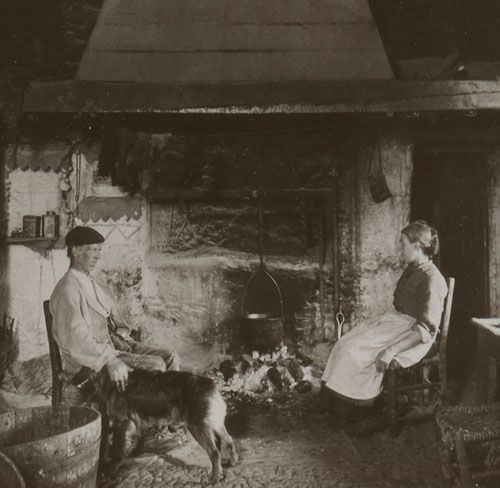

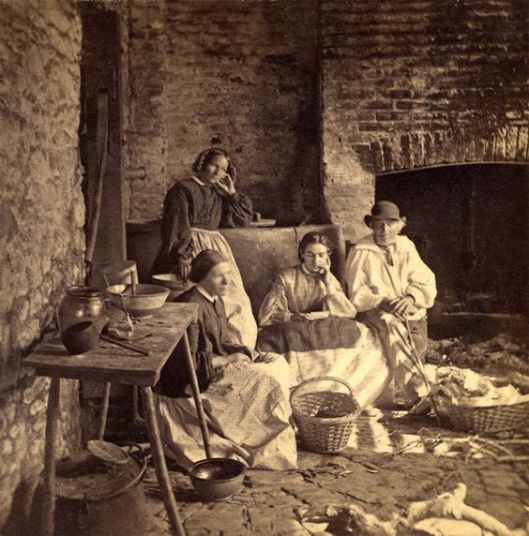

Salads, raw and cooked, date to ancient times, however, here we will look only at ways in which lettuce was cooked. It was put into soup, made into ragout, cooked with green peas, etc. Elizabeth Lea [1859] had this advice for her readers, “Where there is a large family, it is a good and economical way to cut the fat of ham in small pieces, fry it, and make a gravy with flour, water and pepper to eat with lettuce. To cook lettuce you must fry a little ham; put a spoonful of vinegar into the gravy; cut the lettuce, put it in the pan; give it a stir, and then dish it”. Your author remembers the delight of eating this prepared by her aunt Dora, who was a master of the “use what’s in the garden and larder” method of cooking before it became trendy with preppers.

TO MAKE GREEN PEASE SOUP. “The New Book of Cookery”. 1782. Take a small knuckle of veal, and a pint and a half of old green pease; put them in a saucepan with five or six quarts of water, a few blades of mace, a small onion stuck with cloves, some sweet herbs, salt, and whole pepper; cover them close, and boil them; then strain the liquor through a sieve, and put it in a fresh saucepan, with a pint of young pease, a lettuce, the heart of a cabbage, and three or four heads of celery, cut small; cover the pan and let them stew an hour. Pour the soup into your dish, and serve it up with the crust of a French roll.

EGGS WITH LETTUCE. “The Art of Cookery, Made Plain and Easy. Glasse. 1786. Scald some cabbage-lettuce in fair water, squeeze them well, then slice them and toss them up in a saucepan with a piece of butter; season them with pepper, salt, and a little nutmeg. Let them stew half an hour, chop them well together; when they are enough, lay them in your dish, fry some eggs nicely in butter and lay on them. Garnish with Seville orange.

TURKISH MINCE. “Domestic Economy and Cookery”. 1827. Mince hard [boiled] eggs, white meat, and suet in equal quantities, season with sweet herbs and spices, mix it with boiled chopped lettuce, bread crums [sic], a little butter and a raw egg or two; dip lettuce, vine, or cabbage-leaves into boiling water, roll up the mince in them, and fry them of a nice light brown, or bake them in a quick oven, buttering them from a buttering pan, which is a better method than laying on bits; when rolled up for frying, fix the leaves with a little egg; meat may be used instead of egg.

LAITUES AU JUS. “How to Cook Vegetables in one Hundred Different Ways”. 1868. Blanch the lettuces for about five minutes in boiling water, drain them; place some nice slices of bacon in a stewpan; lay the lettuces upon them; add sufficient strong gravy [broth]; simmer for a quarter of an hour, and serve with the strained gravy.

LAITUES FARCIES. “How to Cook Vegetables in one Hundred Different Ways”. 1868. Remove the outer leaves from some good large white lettuces, blanch these for a few minutes in boiling water; drain them; make them hollow by cutting out from the stalk end; fill them with a very good white forcemeat, and stew them gently in consommé, or braise them. Serve with the gravy poured over.

LETTUCES—LAITUES AU LARD. “The Treasury of French Cookery. 1866. The salad being made, salt and pepper are added in the requisite quantities. Cut bacon up in small dice. Melt it in a heater [cook]. Pour it very hot over the lettuces. A little vinegar is immediately put into the heater, and when warm is poured over the salad.

LETTUCE SOUP. “The Master Books of Soups”. 1900. 2 pints veal stock, 1 large head of lettuce, 1 oz. butter, 1 oz. flour, 1 tablespoon lemon juice, salt and paprika.

Cook lettuce in 1 pint of the stock and press through a sieve. Heat butter in a pan and add flour and the other 1 pint of stock. Cook till smooth and creamy. Add lettuce pureé, season to taste, re-heat, add lemon juice, and serve.

“Inferior heads, or the lettuce which does not form heads, is very nice if cooked just like spinach and dressed with cream. Some varieties which have large white veins and mid-ribs may be made to serve a double purpose. Strip out the thin parts of the leaf for use in the salads and then cook the stems and dress them just like asparagus. It will make a substitute for asparagus which will go unsuspected with a good many people”. – Cutler. 1903.

See: Vilmorin-Andrieux, “The Vegetable Garden”, 1920. Randolph, John, “A Treatise on Gardening”, mid-18th c. Weaver, William Woys. “Heirloom Vegetable Gardening: A Master Gardener’s Guide to Planting, Seed Saving, and Cultural History”. 1997. Weaver. “100 Vegetables and Where they Came From”. 2000. Lindquist, K. “On the Origin of Cultivated Lettuce”. Landskrona, Sweden. April 1960. Eaton, Katherine. “Ancient Egyptian Temple Ritual: Performance, Pastterns, and Practice”. 2013. Cookery books listed above.

You must be logged in to post a comment.