Researching who was “the” first to introduce something to North America is a very laborious process, and one for which there is sometimes no definitive answer. In previous centuries, when someone encountered a new plant or animal, it was to them, the first, but because there was no instantaneous exchange of information it may have simply been the first that they knew of, and not necessarily the first to arrive on our shores. The Emden goose is just such a case. Two men have been credited with introducing the geese to the U.S., both of whom were capable breeders, but only one could have been the first.

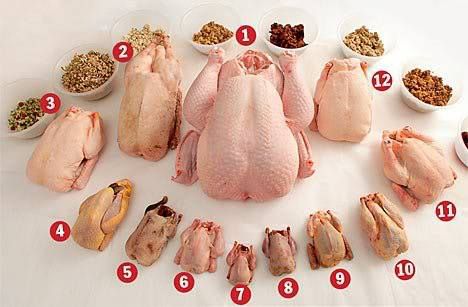

First, we should note that in the earliest years of the 19th century the Emden was known as the Bremen goose in America because that was the port from which they were shipped. The town of Bremen had no more to do with raising geese than any other European town of the day. Nevertheless, to research the earliest North American history of the Emden is to search for the Bremen.

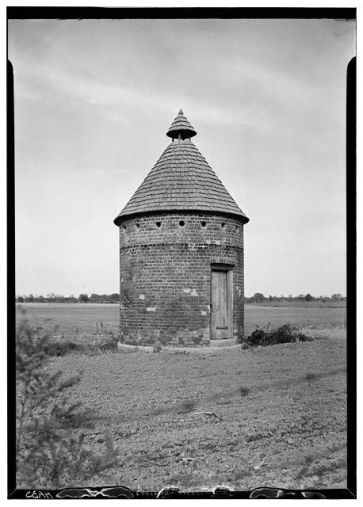

The port at Bremen, Germany is one of the oldest and most successful in Europe. Market rights were conferred on Bremen in 965 and the increase in mercantile activities brought about an economic boom by 1358. By the 18th century it was a major point of departure for emigrants and cargo alike.

Two accounts published prior to 1823 say Mr. James Sisson of Warren, Rhode Island imported geese. The first did not specify what part of Europe the geese came from or what they were called.

“The Plough Boy and Journal of the Board of Agriculture”, [Dec. 23, 1820] contained the following brief notice. “James Sisson, Esq., of Warren, has lately received from the north of Europe two pairs of geese, of such size that when fatted and dressed they frequently weigh upwards of 30 pounds a piece”.

The second piece from the “American Farmer”, Sept. 13, 1822, said Mr. Sisson had geese “brought from Bremen” (the port) in Nov., 1822; it still did not call them the Bremen geese or say where they were raised. Since Mr. Sisson, himself, gave a later date for his importation of the Bremen geese (known to the English as the Emden) his first purchase in 1820 could have been a different breed altogether. In fact, Lewis Wright said, “The naturalists of Embden, and others, do not consider the Embden represents a distinct breed. The geese on the north coasts of Holland and north-western Germany, and the white Flemish goose bred in Belgium and northern France, may all be considered to be of much the same race. The ordinary birds of Friesland also resemble in many respects the variety known as Pomeranian, especially when the latter are white”.

Not nearly as much was published about Mr. Sisson as the second gentleman in our study, but he was recognized as a capable agriculturist as evidenced by an article in “The New England Farmer’s Almanac”, published Sat., August 24, 1822. “He is always seeking improvements in what is most useful to his fellow-citizens, viz. Orchards, the introduction of new kinds of Grain, the best mode of cultivating his farm, &c.”

Almost ten years later an issue of “A New Family Encyclopaedia” contained an account of Mr. Sisson’s Bremen geese. “They [Bremen geese] were first imported, we believe, by Mr. James Sisson, of Warren, (R. I.) who received a premium, in October, 1826, from the Rhode Island Society for the Encouragement of Domestic Industry, for the exhibition of some geese of this breed.”

Supporting the 1826 date for Mr. Sisson’s importing of the geese is an article from the “Genesee Farmer”, dated June 9, 1832, in which Mr. Sisson is quoted from a letter that he wrote to Mr. James Deering published in the “New England Farmer”, vol. iv page 44. “In the fall of 1826, I imported from Bremen, (north of Germany,) 3 full blooded perfectly white geese. I have sold their progeny for three successive seasons; the first year at $15 the pair, and two succeeding years at $12. They, “lay in February and set and hatch with more certainty than the common barnyard goose, will weigh nearly, and in some cases quite twice the weight, have double the quantity of feathers, never fly, and are all of a beautiful snowy whiteness. I have sold them all over the interior of New-York; two or three pairs in Virginia; as many in Baltimore, North Carolina, and Connecticut, and in several towns in the vicinity of Boston. I have one flock half-blooded that weigh on an average, when fatted, thirteen to fifteen pounds; the full blooded weigh twenty pounds”.

“Large Geese.—We yesterday saw in a wagon a pair of young geese, raised by James Sisson, Esq. of Warren, of very large size, being now only three months old. The breed was imported from East Friesland last fall, in the ship North America, Capt. Child, who asserts these geese frequently grow to upwards of twenty pounds dressed. They are very full of soft fine feathers, which is an article of exportation from that country, and very much sought for in Germany, Holland, and England. These geese are the first of this breed which has ever been imported into the United States. –Prov. Pat.” – “The New-York Farmer, and Horticultural Repository”, Vol. 1. June 1828.

For Sisson’s geese to have been brought over the previous fall they would have come in the fall of 1827, the above article being published in June of 1828. There are numerous accounts published from the 1830’s through the 1850’s that support the 1826/7 date.

In 1837, Mr. Sisson received a premium from the Rhode Island Society for the Encouragement of Domestic Industry for his geese which he sold for $6. per pair, half what he had formerly asked. The editor noted that Col. Jaques of the Ten Hills Stock Farm, Charlestown, Mass. offered them at the same price. – “New England Farmer, and Horticultural Journal”. May 23, 1837.

Here we add John Giles, of Providence, R. I. to the mix although no account was found suggesting he’d been the first to own them like the other two gentleman. He had geese imported from Bremen at just about the same time as Mr. Sisson. Both men advertised the geese for sale in various New England publications. Giles was a Vice-President of the New England Society for the Improvement of Domestic Fowls as was Col. Samuel Jaques, the next subject in our discussion. It is obvious the three men knew each other and they may have purchased stock one from another. – “The New England Farmer”. March 16, 1850.

John Giles was a successful livestock breeder as was evidenced by the number of times he is found on lists of premiums earned from the Rhode Island Society for the Encouragement of Domestic Industry fairs. On Sept. 26, 1844, Giles took prizes for his Leicester buck, four Leicester ewes, a Marlin boar, the best milk cow, the best three year old heifer, and the best two year old heifer. – “New England Farmer”. Oct. 16, 1844.

Samuel Jáques, Jr., Esq. wrote in a letter from Ten Hills Farm, near Boston, dated Dec. 12, 1850, an account of Bremen geese brought to the U.S. by his father, Col. Samuel Jáques, Sr., in 1821. “…In the winter of 1820, a gentleman, a stranger, made a brief call at my father’s house; and, in course of conversation, casually mentioned, that, during his travels in the interior of Germany, he had noticed a pure white breed of Geese, of unusual size, whose weight, he supposed, would not fall much short of twenty-five pounds each, providing they were well fed and managed. At that period, a friend of my father’s—the late Eben Rollins, Esq., of Boston—kept a correspondence with the house of Dallias & Co., in Bremen, and at his request, Mr. Rollins ordered, through that firm, and on my father’s account, two Ganders and four Geese of the breed mentioned by the Stranger gentleman. The Geese arrived to order in Boston, in the month of October, 1821; and I append a copy of “Directions relative to the Geese from Bremen,” given to the captain of the ship in which they arrived. I hold the original in my possession…

Ever since my father imported the Bremen Geese, he has kept them pure, and bred them so to a feather—no single instance having occurred in which the slightest deterioration of character could be observed. Invariably the produce has been of the purest white—the bill, legs, and feet, of a beautiful yellow. No solitary mark or spot has crept out on the plumage of any one specimen, to shame the true distinction they deserve of being a pure breed: like, with them, always has produced like. The original stock has never been out of my father’s possession; nor has he ever crossed it with any other kind, since it was imported in 1821.”

The instructions given to the captain were not of Earth-shattering importance as far as goose rearing goes, consisting mainly of notations on how large a pen it took to get the geese through the voyage without any serious injury and on feeding. The letter written from Emden on the 17th of August, 1821 documents the date of Jaques’ purchase. It reads, “…they ought to have constantly fresh water in abundance; a quantity of good sand and muscle scells, [shells,] serving for their digestion, must be put into their feed-box; there ought to be always sand and straw below in their cage for litter; ls above the cage, as the birds perish otherwise by insects. The geese must be feeded; [sic] they used to pick the straw from above down to the feet. The Geese must be feeded with good clean oats, and sometimes with cabbage leaves.”

He gave an account of the name Bremen in his account. “Having had the breed of Geese in question sent him from Bremen, my father named them after that place; but English writers call this variety the ‘Emden Geese’. It will be seen from what I have stated above, that my father was the original importer of this description, and therefore is entitled to the credit of first introducing it to the United States. It is certain that he had the Bremen Geese in his possession, at least five years prior to the time when Mr. James Sisson, of Rhode Island, imported his, and since 1821 my father has furnished this breed to many parties residing in almost every State in this Union, as also in Canada and Nova Scotia.” – Dixon, Edmund Saul. “A Treatise on the History and Management of Ornamental and Domestic Poultry”.

Samuel Jacques, Jr. placed an advertisement in “The New England Farmer” for 24 large Bremen Geese saying, “The original stock of these geese was imported by Ebenezer Rollins, Esq. of Boston”—the same Eben Rollins whom he said in his letter imported the geese for his father. “The New England Farmer”, Nov. 10, 1826.

Rollins was a prominent merchant in Boston, a founder and member of the first Board of Trustees of Groveland or E. Bradford Academy, and a bank and insurance director. No evidence was located to indicate he was involved in agriculture or animal husbandry. He died in Havana, Cuba on March 2, 1831.

That Col. Jacques was quite knowledgeable on a number of agricultural subjects, is evidenced by a notice found in “The Farmer’s Monthly Visitor” in which the editor praised his experience and requested him to share his knowledge of milk cows with their readers.

For Samuel, Jr. to say a stranger appeared at his father’s home and told them about the geese is not at all unusual for Col Jaques owned the famous Ten Hills Farm first owned by Gov. Winthrop of Massachusetts. The farm had been a show place for roughly two centuries by the time Col. Jaques purchased it, and because of his reputation as a knowledgeable breeder of livestock and plants, strangers appeared at his door on a regular basis, sometimes to inquire about making a purchase and at other times just to admire the efficiency with which Ten Hills Farm was run.

In his information given to Mr. Dixon for “A Treatise on the History and Management of Ornamental and Domestic Poultry”, Samuel Jacques, Jr. noted the incredible laying ability of the Bremen. “I find, by reference to my father’s notes, that, in 1826, and in order to mark his property indelibly, he took one of his favourite imported Geese, and, with the instrument used for cutting gun-waddings, made a hole through the web of the left foot. This was done on the 26th of June: and now, in 1850, the same Goose, with the perforation in her foot, is running about his poultry-yard, in as fine health and vigour as any of her progeny. She has never failed to lay from twelve to sixteen Eggs every year, for the last twenty-seven years, and has always been an excellent breeder and nurse, as has all of the stock and offspring connected with her. I had the curiosity to weigh one of her brood of 1849, when nine months old exactly, and his weight, in feather, sent up 22 lbs. in the opposite scale. This hugeous Anser has been preferred to breed from, the coming season.”

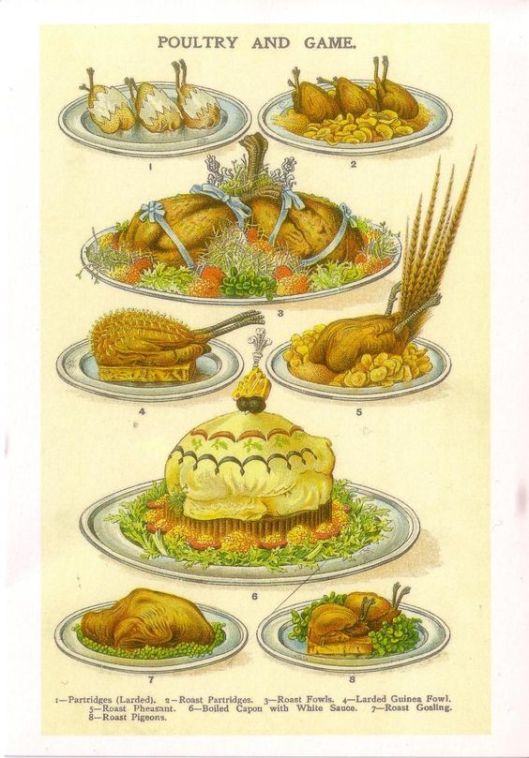

Because Col. Jacques kept such immaculate records, his son was able to relay that in 1832 a bull-dog killed several of his father’s Geese, and, among them, the two Ganders originally imported after which he used their offspring to mate to the females. He raved about the culinary standards of the Bremen saying that some of the keenest epicures of the time had declared the flesh of the Emden equal to, if not superior to, the “celebrated Canvas-back Duck”.

He went on to describe in detail how the geese were encouraged to lay, what they ate, care of the young goslings, etc., facts he would have known only by referring to the detailed diaries kept by his father.

Col. Jaques’ obituary published in “The New England Historical and Genealogical Register” in July 1859 is fascinating. He was the fifth generation descended from Henry Jaques who came from England to settle in Newbury in 1640. He was born in Middlesex on Sept., 12, 1776 and died at his farm on March 27 at age 83. The obituary notes that he was particularly noted for experiments in breeding domestic animals and fruit. He developed cows which he named Cream-pots and won numerous premiums at stock shows for cows, horses, and sheep. He developed a peach which bore his name and he was chief marshal of a procession at the laying of the corner stone of the Bunker Hill Monument by Gen. La Fayette June 17, 1825. He was Inspector General of Hops for Massachusetts from 1806 to 1837. He kept a diary which numbered some forty to fifty volumes in which he claimed to have written something almost every day.

Samuel Jaques, Sr. became Col. Jaques during the War of 1812. “Colonel Jaques, at first major, acquired his title by long service in the militia, and was engaged for a time during the hostilities of 1812 in the defense of Charlestown bay, and was stationed at Chelsea. He was in manners and habits of the type of the English country gentleman.” – “Anecdotes”, by Mrs. Alida G. Sellers. 1901.

A brief history of the farm prior to Col Jaques’ ownership reveals the militia went to Ten Hills Farm for target practice in the summer and several times per year the grounds were open to neighbors to help themselves to cherries, pears, and other fruit from the orchards.

It was from Ten Hills that Gage’s night expedition to seize powder in the Province Magazine began in 1774. When the Continental troops fell back from Breed’s Hill, they made a stand at Ten Hills but retreated. The British then took control of the home using the east parlor to stable horses and the rest of the house became quarters for men and officers.

The home remained uninhabited for some time following the war until purchased by General Elias Hasket Derby in 1801. It changed hands a few times until Col. Jaques, a descendant of Sire Rolande de Jacques, a feudal baron in Normandy, France, bought it in 1832. Having exhibited a patriotic nature on numerous occasions, it is not surprising that he took great pride in the history of the manor house at Ten Islands.

“The holes in the east parlor where the spikes were driven in by the Englishmen to tie their horses were left unfilled, however, and, much to the disgust of the family, the colonel always showed them to his visitors by poking his fingers through the expensive paper into the holes.” –

Someone in Col Jaques position naturally knew the movers and shakers of the day, men like Daniel Webster with whom he remained in close contact, but his company also drew the likes of the eminent biologist and geologist, Professor Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz. Agassiz had a keen interest in natural history and is known for his work in that field.

The Bremen goose was only one of the valuable animals raised by Col. Jaques. He was noted for his breeding of cattle, and in fact, family members felt he held fast on his deathbed until two calves were born, products of one of his last breeding experiments. “He had been given up by the doctors weeks before, but so great was his interest in the birth of the animals that his strong will kept him alive. They [calves] were born in the morning; in the afternoon they were washed and brought to his room. Each in turn was lifted on the bed, and after he had examined them carefully, he laid back on his pillow and in a few hours passed away”.

As to who first imported the Bremen geese, this writer’s money is on Col Jaques because he kept such meticulous records on purchases of livestock and the details of the feeding and breeding of each animal he owned. Mr. Sisson, on the other hand, is not documented as having produced records other than the quote in the letter to Mr. Deering and, by his own account, was sloppy in his breeding habits allowing the Bremen geese to interbreed with the common farmyard goose. In that letter he was quoted as buying the geese some years after they were brought over by Col. Jaques.

By the late Victorian era some journals admitted that accounts giving credit to Mr. Sisson published several decades earlier had been in error. The following quote was penned by Caleb N. Bement. “We were always under the impression that Mr. James Sisson, of Warren, Rhode Island, was the first importer of these superior geese; but it appears incorrect from the following account published in the “New England Farmer” [the account by Sisson saying he brought over geese in 1826].

A bulletin published in February, 1897, supported Samuel Jaques, Jr.’s claim that his father was the first and quoted the letter explaining to the captain how to care for the geese Col. Jaques imported in 1821. That editor also quoted from the letter that it was written from Emden on the 17th of August, 1821. The next paragraph states in 1826, James Sisson, of Warren, R. I., imported a trio from Bremen, “and others were imported about the same time by John Giles of Providence, R. I.”

Bibliography:

Mrs. Alida G. Sellers (born Jaques), Boston, Mass. December 19, 1900. Account given in Somerville. Historical Society. , 1903.

“Bulletin”. Agricultural Experiment Station, University of Rhode Island. Feb. 1897.

Numerous magazine and newspaper articles including those above.

New England Farmer. April 11, 1832.

The Cultivator. March 1845. Albany.

Drake, Samuel Adams. “Historic Mansions and Highways Around Boston”. 1899.

California Farmer and Journal of Useful Sciences. Vol. 11, Number 15, 12 May 1859.

Bennett, Caleb. “The American Poulterer’s Companion”. 1863.

The Boston Directory Containing the Names of the Inhabitants, their Occupations, Place of Business, and Dwelling-houses”. Boston. June, 1807.

Rollins, John R. “Records of Families of the name Rawlins or Rollins in the United States. 1874. Lawrence, Mass.

- S. Congress. “Register of Debates in Congress”. Washington. 1831.

“New England Farmer”, Vol. 3. Oct. 1824.

– “A New Family Encyclopaedia”. 1831.

http://www.mygermancity.com/bremen

Wright, Lewis. “The New Book of Poultry”. 1902. London.

You must be logged in to post a comment.