Tags

Gentle readers, today’s post departs from gardening and cooking as sometimes happens. I hope that some of you find it useful.

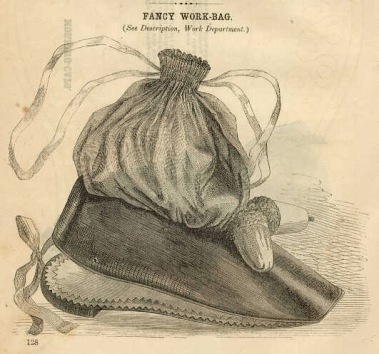

To research an 18th or 19th century lady’s collection of sewing implements it helps to know what the collection was called during that time. While one can research individual tools, the container that held them, always ready for easy availability, was most often called a work bag. References are found from articles and books published as early as the 1700’s.

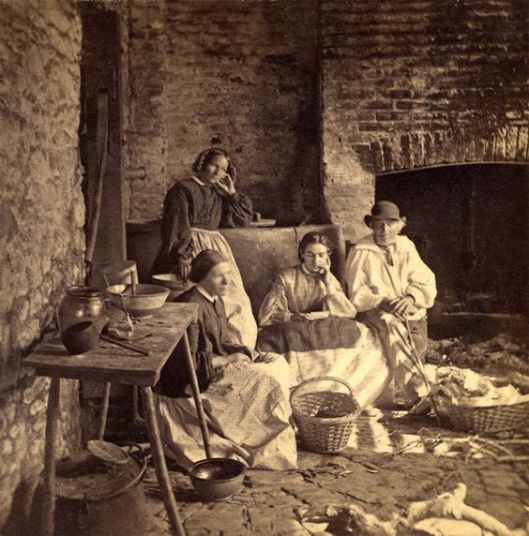

It was important that every woman knew how to sew and embroidery. More well-to-do women and girls might have worked on more delicate garments and smaller fancy items such as handkerchiefs, doll clothes, or delicate underpinnings, but they were still expected to perfect their sewing skills. Most girls learned embroidery stitches by making samplers.

Work-bags ranged from strictly utilitarian to being knitted or made of satin and decorated with tassels, embroidery, and other embellishments and were often made to give as gifts to a friend or loved one. They were often made to sell at church bazaars.

Women commonly carried work-bags with them as they visited friends, sometimes working on their needlework as they carried on their conversations. Young girls often had their own workbags.

“. . . and brought, for each of the little girls, a present of a sattin [sic] work-bag ornamented with gold. There was in each bag a needle-book, and a piece of muslin, on which was drawn a pretty design”.

In addition to sewing tools a work bag was also used to carry everyday items as one might use a tote bag today. It might have contained items such as keys, a piece of jewelry, letters or notes, money, toothpick cases, books, sewing, knitting, or embroidery projects, gloves, handkerchief, etc. or it may, on occasion, have been used to gather nuts or flowers. A housewife (a sewn sewing kit of sorts used for holding pins, needles, buttons, etc.) was often part of the contents of a workbag. In 1841 an article was published about the early use of potatoes in which a woman of 45 years said the first potato they ever saw was kept in her mother’s work-bag to await the season for planting.

Reading material and calling cards were often kept in work-bags. “I did intend reading something to the children,” said their mother, as she drew a paper from her work-bag”. The work bags also held scissors, a bodkin, and needles.

Sewing is done by choice today but in times past clothes were made and mended and the tools to do the job were in constant use. A woman valued them because replacing them was a hardship. A poem [published 1831] entitled “Careless Matilda” addresses a young lady who haphazardly leaves her sewing tools scattered about, never knowing where anything is.

“Again, Matilda, is your work astray,

Your thimble gone! Your scissors, where are they?

Your needles, pins, your thread, and tapes all lost—

Your Housewife here, and there your work bag tost [tossed]”.

The following quote demonstrates the importance of carefully storing away a work-bag for the next time it was needed. “. . . then Lucy’s mother kissed her, and said to her, put your work into your work-bag, and put your work-bag into its place, and then come back to me.”

My workbag is made of toile after a pattern published in Godey’s Lady’s Book. It is a good size with pockets sewn around for keeping various items together. It has a drawstring closure. It has held everything documented above at one time or another. Researching workbags reminded me how much I need to reorganize mine and be as faithful about keeping my sewing implements together in it as my predecessors were. At my age one would hope to be better organized than I generally am.

You must be logged in to post a comment.