Tags

Keeping supplies from which to feed the crew on a late eighteenth or early nineteenth century sailing vessel was an art which was part culinary and part science though those doing it wouldn’t have viewed their efforts as either. Janet MacDonald’s in depth look at “Feeding Nelson’s Navy” shows how the food was procured by the Victualling Board or captains in port, stored, loaded onto the ship, preserved, cooked, and served for the officers and messes onboard ship. While common sense might dictate, with her research we can document the sort of supplies kept on the ships. By looking at receipts for ships captains in Hannah Glasse’s “The Art of Cookery, Plain and Simple” (1774) and possessing a general knowledge of 18th century food preparation we can envision what made dishes the men ate.

The first receipt in Glasse’s chapter, “Recipes for Captains of Ships”, is “To Make Catchup to Keep Twenty Years”. With today’s inferior packaging this claim may seem dubious at best, however, I have no trouble believing it kept until it was used up. It was made with strong stale beer, anchovies, shallots, mace, cloves, whole pepper, ginger, and mushrooms. It was cooked until it reduced by half, strained, and bottled. This would have seasoned any number of dishes.

Her fish sauce was similar, but instead of mushrooms contained horse-radish, white wine, lemon, anchovy liquor, red wine, and similar spices.

Meat drippings were an integral part of cooking at home or on the sea, but particularly so on ships where access to fats and oils was often limited. Glasse gave explicit instructions to the sea cooks on keeping the drippings fresh. The beef dripping was boiled in water, cooled, then the hard fat taken off and the “gravy”, or gelatinous material adhering to the underside of it, was scraped off. This was to be repeated seven times more before adding bay leaves, cloves, salt, and pepper to it. It was sieved and allowed to grow cold in the pot. She advised turning the pot upside down onto a flat surface to keep out the ever-present rats.

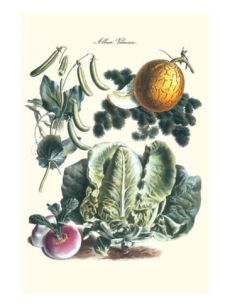

There were receipts for pickling and powdering mushrooms which are found in most any cookbook from the era. (Plagiarism was common amongst early cookery writers.) Her “To Keep Mushrooms Without Pickle” is rather interesting. She instructed cooking the mushrooms with salt, draining them and drying them on tin plates in a cool oven. When perfectly dry they were put into a stone jar, tied down tight and kept in a dry place. “They eat deliciously, and look as well as truffles”.

For change she discussed drying artichoke bottoms and reconstituting them in water for adding to sauces or to flour and fry them. The latter was to be served with melted butter. Her “fricasey” of artichoke-bottoms directed the cook to lay them in boiling water until tender, and put to them half a pint of milk, a quarter of a pound of butter rolled in flour, stir it “all one way” till quite thick then add a spoonful of mushroom pickle. The artichokes were put into a dish and the sauce poured over. Documents show that ships carried cows, or more often, a sheep or goat aboard for fresh milk.

Crew members were known to catch fish which was a welcome meal. Glasse told the cook how to fry the fish in beef dripping and serve with a sauce. Her method of baking fish was quick allowing the cook to concentrate on other parts of a meal. “Butter the pan, lay in the fish, throw a little salt over it and flour; put a very little water in the dish, an onion and a bundle of sweet-herbs, stick some little bits of butter or fine dripping on the fish. Let it be baked of a fine light brown; when enough, lay it on a dish before the fire, and skim off all the fat in the pan; strain the liquor, and mix it up either with the fish-sauce or strong soop [sic], or the catchup.

For soup, the cook was to refer to a previous chapter aimed at home cooks.

Puddings were salt beef or pork, mutton (butchered onboard), apples or prunes rolled in pastry, put into a pudding bag, and boiled in like manner.

Currants and raisins were among the stores kept on the ship and these were utilized to make a suet pudding. There are two receipts for Oatmeal puddings with raisins and/or currants.

The liver of an animal killed onboard was made into a pudding with the liver cut fine and mixed with suet, crumbs of bread or biscuit (hard cracker), sweet herbs, nutmeg, pepper, salt, anchovy and butter, then put into a crust and boiled.

Rice pudding was made by: 1. boiling rice in a cloth, taking it up and adding nutmeg, butter, and sweetener and boiling it again. It was served with a sauce made of butter, sugar and a little white wine. 2. Baking it in a buttered pan with similar ingredients.

There were methods for making both soup and pudding from dried peas found in rations.

Harrico of French beans is brilliant in its use of ships stores. A pint of the “seeds of French beans, which are ready dried for sowing”, were boiled for two hours, drained, reserving the liquid, and added to onions fried brown in butter, pepper and salt, and made to the thickness desired. “When of the proper thickness you like it, take it off the fire, and stir in a large spoonful of vinegar and the yolks of two eggs beat. The eggs may be left out, if disliked.”

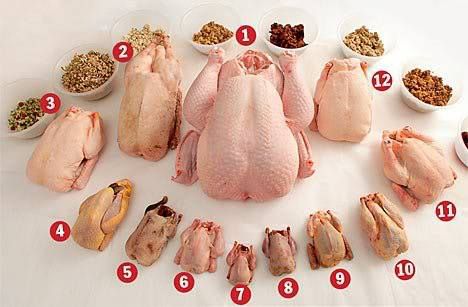

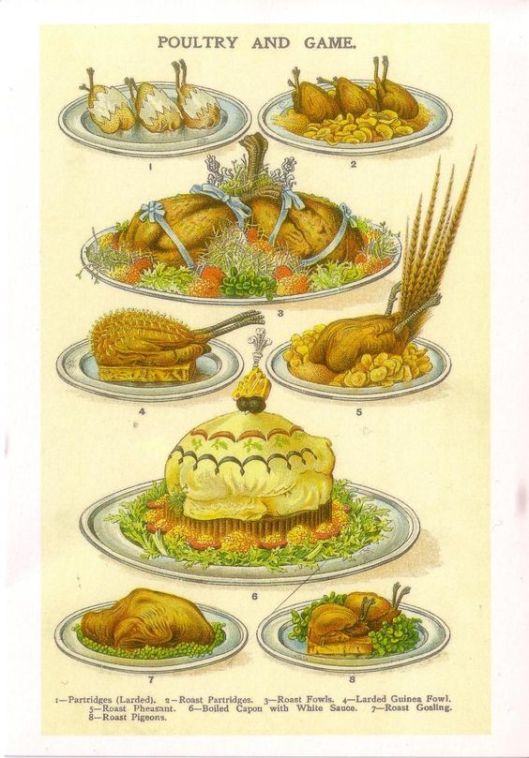

Ships often housed poultry for the eggs and for cooking. They were readily available in most ports. At whatever point the cook felt proper to butcher some of the fowl the evening meal could have been made into a pie. Glasse says to fill the paste with bacon or cold boiled ham, sliced, and season it with pepper and salt and add a little water. A pastry lid was put on and the pie baked for some two hours. Seasoned gravy was poured in just prior to serving it.

Janet MacDonald found no mention of potatoes among the foods available from the Victualling Board until the 19th century, however, either they sometimes purchased them from locals where they stopped or Hannah Glasse wasn’t aware they weren’t available onboard ships. Her Cheshire pork pie for sea was a crust filled with layers of salt pork and sliced potatoes seasoned with pepper.

Her Sea Venison was freshly killed mutton boiled in the sheep’s blood and hung to dry before roasting. She did note this process depended upon the weather and how long the meat could be kept without spoiling.

She concluded the chapter with a receipt for dumplings the size of a turkey’s egg made of bread crumbs, beef-suet, nutmeg, sugar, and two spoonsful of sack (wine). They were boiled and served with a sauce of butter and sack with a little sugar strewn over.

She referred the reader to her chapter on soups and broths. The officers’ cook might have been able to read her book and shared ideas with the mess cooks, but more likely an officer might have purchased or borrowed a copy from which he instructed the cook.

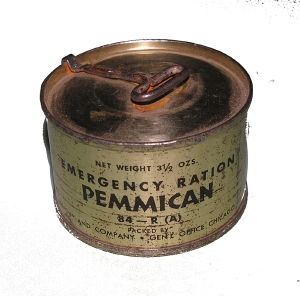

The most useful receipt may have been for making Portable soup and Pocket soup which was cooked down to “glue” and when ready to prepare it reconstituted with water to make gravy and sauces as well as broth and soup.

Good day, gentle readers, I hope you find this brief advice useful in stocking your home larder should you have an interest in any degree of self-sufficiency. I leave you with wishes for Blissful Meals.©

You must be logged in to post a comment.