Tags

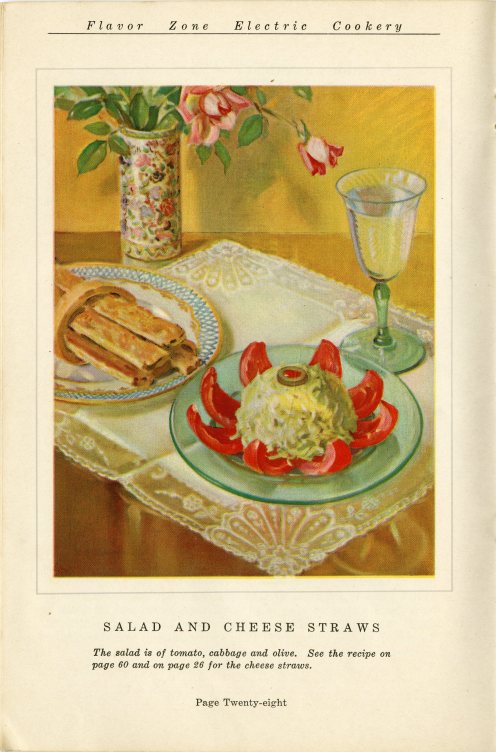

Photo: William Woys Weaver, Roughwood Seed Collection

I once had someone who was viewed as an amateur historian tell me that people did not eat dried beans in the 18th century. What? I’ve never forgotten that and today we will debunk that theory.

The earliest description this writer found for a white-seeded bean that matches the description of what was later called the case-knife bean was written by Nicholas Culpepper in 1666. “…but white is most usual; after which come long and slender flat cods, some crooked, some straight, with a string as it were running down the back thereof, wherein are contained flattish round fruit made to the fashion of a kidney…”.

Amelia Simmons was perhaps the earliest cookery book writer to document white beans for drying (1796) and Simmons listed a “clapboard” bean which some think was the case-knife. She advised they must be poled and were, “the easiest cultivated and collected, are good for string beans, will shell”.

Philip Miller said in 1775 the Dutch White Beans were much the sweetest for the table. He thought them “extream [sic] windy Meat” and recommended preparing them in the Dutch fashion of half boiling them then “you husk them and stew them… they are wholesome food”.

John Reid wrote of beans in 1683, “Beans and peas boyled with savory and thym[e]…served up with sweet butter beat amongst them and set a little on a coal or chaffing boyl [sic]”. – “The Scots Gard’ner”.

A farmer wrote in 1840 that the “prettiest” way to grow dry beans was to raise white pole beans and, “The common case-knife beans are excellent for this purpose”. Twenty-three years later Fearing Burr told his readers the case-knife was “common to almost every garden” and it remained so into the early 20th century. Today the white-seeded variety of case-knife bean isn’t as common, at least by that name, but close versions can be found.

“Some Dutch case-knife beans did come up and grew finely…In good time they were heavily loaded, and they were of rich and splendid flavor, so much so I forbade wife cooking any more, having visions of acres of beans and a big bank account”. One will pity this poor farmer when he explained that a mere few days before he went to pick his dried beans they had been beset upon by weevils.

“The manner of saving the seeds of these plants, is to let a few rows of them remain ungathered in the height of the season; for if you gather from the plants for some time, and afterwards leave the remaining for seed, their pods will not be near so long and handsome, nor will the seed be so good. In autumn, when you find they are ripe, you should in a dry season pull up the plants and spread them abroad to dry; after which you may thresh out the seed and preserve it in a dry place for use”. – Miller, Philip. “The Gardener’s Dictionary”. 1768.

Buist [1805-1880] proclaimed the Dutch Case-knife to be an excellent pole bean producing a good crop of fine flavor and much earlier for the table than either the Lima or Carolina. “It can be used either in or without the pod; it is also adapted for winter use”.

Mr. W. F. Massey submitted information on white beans and their culture in the hot humid South for the Southern Planter and Farmer in 1900 saying they produced more damaged beans than when planted in the North. He stated the best white beans he’d ever tried growing in the South were the Dutch Case-Knife beans. “This is a pole bean, but not a rampant climber, and in my boyhood was commonly planted in the corn field and allowed to climb on the stalks in a portion of the field so as to give a supply for shelling in winter. It is a flat bean, similar in shape to a small lima, but smaller still. There is no shelled bean of better quality.”

As for the method of growing these beans they could be trellised or staked. The following would make a nicer presentation than row staking. “Strike out a dozen (or more) circles on the ground, as large as a cart wheel. Put a wheel barrow load of manure into it and spade it up with the earth. Drop the seeds in the circle, on the outer edge of the hill, say six inches apart. Then insert eight or ten poles just within the circle, at equal distances from each other, and tie the tops of the whole together-forming a cone. Cover up the seed and wait the result.

Each of these hills will yield you a peck or a half bushel of dry beans next fall—which if you have but a dozen such hills, will give you, perhaps half a dozen bushels. This will be enough for your purpose. By this course, but a little land is occupied. Pole beans will yield very much more abundantly than bush beans, and occupy air, whilst the latter must have the surface of the earth”. – Holmes, Frances. “The Southern Farmer and Market Gardener”. 1842.

This bean was often referred to as Old Dutch White or White Dutch and differs from the brown-seeded variety sometimes sold as Caseknife today. Old cookery books and garden manuals refer to white beans, small white beans, large white beans and great white beans. All agree the white was preferred.

Dr. William Woys Weaver says the Caseknife Bean is perhaps the oldest documented bean in American gardens. Like the farmers quoted above he believes the oldest were white seeded like those grown in the gardens of Thomas Jefferson and the closest variety to the original bean is the Pelzer Schwertebuhne (Palatine Caseknife Pole Bean). He found the beans being grown by the Wendel family of Weilerbach in the Rheinland-Pfalz. He offers the Palatine June Pole Bean in his Roughwood Seed Collection.

As to cooking dried white beans, let’s look at Louis Eustache Ude’s 1814 receipt.

White Beans a la Maitre d’Hotel. “if they are dry, they must be soaked for an hour in cold water, before you boil them. Then boil them in cold water and replenish with cold water also which makes the rind or coat tender. White beans must be well done before you dress them, which is done as follows: trim a stew-pan with a quarter of a pound of fresh butter, a little parsley chopped very fine, and some pepper and salt, over which lay the beans, well drained. Keep moving the stew-pan without using a spoon, for fear of crumbling the beans. Then squeeze the juice of half a lemon and send up quite hot”.

The Shop at Monticello offers seeds of the Caseknife Pole Bean which have white seed like the original and the flattened, slightly curving shape of the beans matches the description above. They are grown out on-site. A packet contains between 20 to 25 seeds and sells for $3.95 plus shipping. 1-800-243-1743.

Johnson’s Home and Garden offers “Old Dutch White Half Runner Bean” seed he says were brought from Germany by original settlers of the Dutch Fork Section of South Carolina. A Half Pound of untreated seed is $3.95 and a pound is $5.95. Johnson’s Home & Garden, 130 Power Drive, Pikeville, KY 41501, phone 606-432-8460.

Roughwood Seed Collection: https://www.roughwoodtable.org/roughwood-seed-collection offers the Palatine June bean seed.

You must be logged in to post a comment.